Learning Objectives

- Explain the fluid mosaic model of cellular membranes, in terms of membrane structure, composition, and dynamics

- Identify the membrane lipids that are unique to each of the 3 domains of life

- Predict how variation in membrane lipid composition affects the fluidity and integrity of membranes

- Predict whether a molecule can diffuse across a cell membrane, based on the molecule’s size, polarity, and charge

- Distinguish among the types of transport (simple diffusion, facilitated diffusion, and active transport), based on their kinetics and energy requirements

- Predict the direction of water transport across the membrane under different conditions of salt and osmolarity

Membrane structure

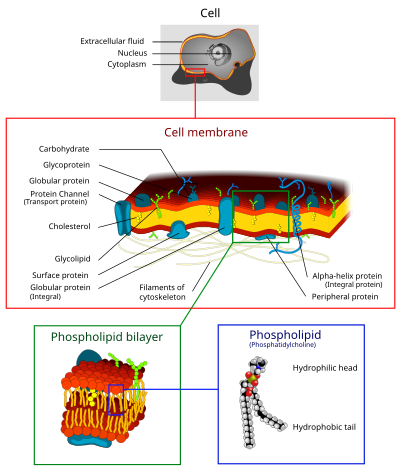

The cell membrane is a fundamental and defining feature of cells. It is composed of a phospholipid bilayer, with the hydrophilic phosphate “head” groups facing the aqueous environment on either side, and the hydrophobic “tails” in middle. The two components of this layer are called “leaflets,” where the inner leaflet is on the cytoplasmic side of the membrane and the outer leaflet is on the extracellular side. The inner and outer leaflets have different lipid compositions.

In a typical cell membrane, 50% of the membrane is made of proteins that are firmly embedded in the hydrophobic lipid bilayer, called integral membrane proteins. Some integral membrane proteins have alpha-helical domains that traverse both leaflets of the membrane (transmembrane domains). Other proteins, called peripheral membrane proteins, are loosely and reversibly associated with membranes, interacting with the polar phosphate head groups. Cell membranes also have carbohydrates, in the form of oligosaccharides, covalently attached to membrane proteins (glycoproteins) or to lipids (glycolipids).

The fluid mosaic model of cell membranes describes how lipids and integral membrane proteins diffuse laterally within the plane of the membrane. While the proteins raft around on and within the membrane, the hydrophobic inner core prevents phospholipids and integral membrane proteins from spontaneously crossing the lipid bilayer or flipping across it from one side to the other.

Membrane lipids differ in the three domains of life

The three domains of life—Bacteria, Archaea and Eukarya—have distinct membrane lipids that pose challenges and offer hints to reconstructing the evolutionary history of life on Earth.

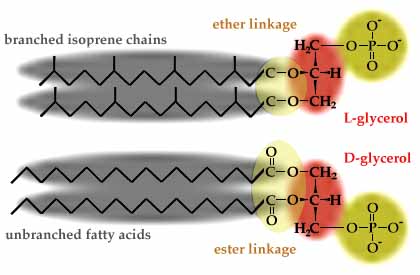

All cells have phospholipids (glycerol-phosphate with two hydrocarbon chains) in their membranes. Bacteria and Eukarya both have membrane phospholipids with fatty acid chains ester-linked to D-glycerol. Archaea, however, have utterly different membrane phospholipids, with branched isoprene chains instead of fatty acids, L-glycerol instead of D-glycerol, and ether linkages instead of ester linkages (see https://www.ucmp.berkeley.edu/archaea/archaeamm.html and https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Archaea). The ether linkages and isoprene chains make Archaeal membranes more resistant to heat and pH extremes.

Current hypotheses suggest that eukaryotic cells arose from a fusion between an archaeal cell and a bacterial cell. Based on DNA sequence similarities, eukaryotic information processing genes are descended from archaea (Allers and Mevarech 2005, Cotton and McInerney 2010), whereas eukaryotic membrane phospholipids synthesis genes and energy metabolism genes appear to have descended from bacteria.

Eukaryotes also have membrane lipid innovations that are not found in either Archaea or Bacteria: sterols and sphingolipids. Sterols (like cholesterol) and sphingolipids (phospholipids with fatty acid chains linked to the amino acid serine instead of to glycerol) are major components of eukaryotic plasma membranes, and together they can constitute 50% of the lipids of the outer leaflet (Desmond and Gribaldo, 2009; sphingolipids are not found in the cytoplasmic side of the plasma membrane lipid bilayer). Sterols are essential in all eukaryotic cell membranes. Sterols reduce membrane fluidity and permeability and increase membrane rigidity and strength. Together with sphingolipids they help organize regions of the membrane into lipid rafts, microdomains in the plasma membrane with increased rigidity, for cell signaling (Lingwood and Simons, 2010).

Sterol biosynthesis is a complex pathway that requires molecular oxygen (O2). Eleven molecules of oxygen are required to synthesize just one molecule of cholesterol (Desmond and Gribaldo, 2009). Therefore, steroid biosynthesis could not have evolved before the Great Oxygenation Event that occurred 2.4-2.5 billion years ago, when free oxygen first began to accumulate in Earth’s oceans and atmosphere. Significantly, this time coincides with the origin of eukaryotes in the fossil record. Evolution of steroid biosynthesis pathways is likely to be a key adaptation in the evolution of eukaryotes.

Not to be left out, bacteria have their own special membrane adaptations in the form of hopanoids, the bacterial equivalent of membrane sterols. Hopanoids have 5 rings and do not require oxygen for their biosynthesis.

Cells regulate membrane fluidity by adjusting membrane lipid composition

The fluidity of a lipid bilayer varies with temperature. At higher temperatures, lipid bilayers become more fluid (think about butter melting on a hot day) and more permeable, or leaky. At lower temperatures, lipid bilayers become rigid (like butter in the refrigerator). For cell membranes to function properly, they must maintain a balance between fluidity and integrity. Fluidity allows movement of proteins and lipids within the membrane, along with membrane curvature, bending, budding and fusion. This dynamism in the membrane has a limit before membrane integrity is compromised, allowing substances to leak into or out of the cell.

Sterols buffer membrane fluidity and permeability over a broad temperature range. In mammals, cholesterol increases membrane packing to reduce membrane fluidity and permeability. Ergosterol in fungi and phytosterols in plants play similar roles in their respective organisms.

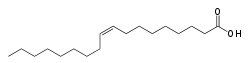

The tails of phospholipids are fatty acids that also affect membrane fluidity. Fatty acids can vary in length and in the number of double bonds in the hydrocarbon chain. Fatty acids with no double bonds in the hydrocarbon chain are called “saturated” because they have the maximum number of hydrogens. “Unsaturated” fatty acids have one or more double bonds and therefore have fewer hydrogens (2 fewer per double bond). Naturally-occurring unsaturated fatty acids are cis-unsaturated. Their remaining hydrogens are on the same side of the molecule, maing a bend in the hydrocarbon chain. Trans-unsaturated fatty acids, with the hydrogens on opposite sides, result in a nearly straight hydrocarbon chain like a saturated fatty acid. Trans-unsaturated fatty acids are rare in nature. They are produced in food processing to partially hydrogenate vegetable oils.

| Elaidic acid is the principal trans unsaturated fatty acid often found in partially hydrogenated vegetable oils.[41] |  | |

|

Oleic acid is a cis unsaturated fatty acid making up 55–80% of olive oil.[42]

| ||

| Stearic acid is a saturated fatty acid found in animal fats. Stearic acid is neither cis nor trans because it has no carbon-carbon double bonds. |

The different structures in different types of fatty acids influence their chemical characteristics and biological effects:

- longer fatty acids are more rigid, reducing membrane fluidity and permeability

- cis-unsaturated fatty acids increase membrane fluidity and permeability by disrupting close packing of fatty acid tails. Cis-polyunsaturated (2 or more double bonds) fatty acids are even more bent and disruptive.

- organisms adapt to cold temperatures by increasing the amounts of cis-unsaturated fatty acids to keep their membranes fluid.

- animal fats, like butter, with relatively low levels of cis-unsaturated fatty acids and high levels of saturated fatty acids, are solid at room temperature

- vegetable oils, with high levels of cis-unsaturated fatty acids, are liquid at room temperature

One way to remember how different lipids affect membrane fluidity or rigidity is that lipids that can pack more tightly (like saturated fatty acids and sterols) make membranes more rigid and stronger, but less fluid. Anything that disrupts close packing of lipids, such as higher temperatures or unsaturated fatty acids with kinks or bends, make membranes more fluid.

Membrane permeability and osmosis

The lipid bilayer is “semi-permeable,” meaning that some molecules can diffuse rapidly across the membrane, while other molecules cross only very slowly or not at all. In general, small uncharged molecules like O2 and CO2 can diffuse across the membrane freely, while charged molecules (Na+, H+) or polar molecules (glucose) cannot. Even water molecules diffuse only slowly across cell membranes because water molecules are highly polar.

Osmosis is the diffusion of solvent (water) molecules across a membrane. Diffusion results in net movement of molecules down their concentration gradient, from an area of higher concentration to an area of lower concentration. In the case of osmosis, water molecules move from the side with lower solute concentration to the side with higher solute concentration. If there is a difference in solute concentrations across the membrane, then solute molecules will try to diffuse across the membrane to equalize solute concentrations. But if the membrane is impermeable to the solute molecules, then water will move to try to equalize the solute concentrations.

Cells are adapted to their aqueous environment in terms of their cytoplasmic solute concentrations. Mammalian cells have cytoplasmic solute concentrations that balance the physiological salt or saline concentrations. Physiologically, mammalian cells are in an isotonic environment, meaning the solute concentrations inside the cell and outside the cell are in balance, so there is no net movement of water across the cell membrane. In a hypotonic solution, the solute concentration outside the cell is lower than inside the cell, so water will enter the cell to try to reduce the internal solute concentration. In a hypertonic solution, the solute concentration outside is higher than inside the cell, so water will exit and the cell will shrivel up.

Membrane proteins and transport

How do cells transport molecules like glucose across the membrane? Membranes have dedicated transport proteins with transmembrane domains. Several transmembrane domains cluster to form channels in the membrane that are specific for various molecules like glucose, phosphate, Na+, H+, Cl-, and even H2O. Water transport is mediated by highly conserved proteins called aquaporins, which are present in all 3 domains of life.

The movement of molecules through protein channels is called facilitated diffusion. The protein channels are highly specific for the molecule, and again results in net transport down a concentration gradient, from a region of high concentration to a region of low concentration.

In many situations, cells move molecules against their concentration gradient! Even when phosphate concentrations outside the cell are very low, cells can transport phosphate into the cell, where the cytoplasmic concentration of phosphate may be much higher. Active transport of molecules against their concentration gradient requires energy, often in the form of hydrolysis of ATP.

Kinetics of transport

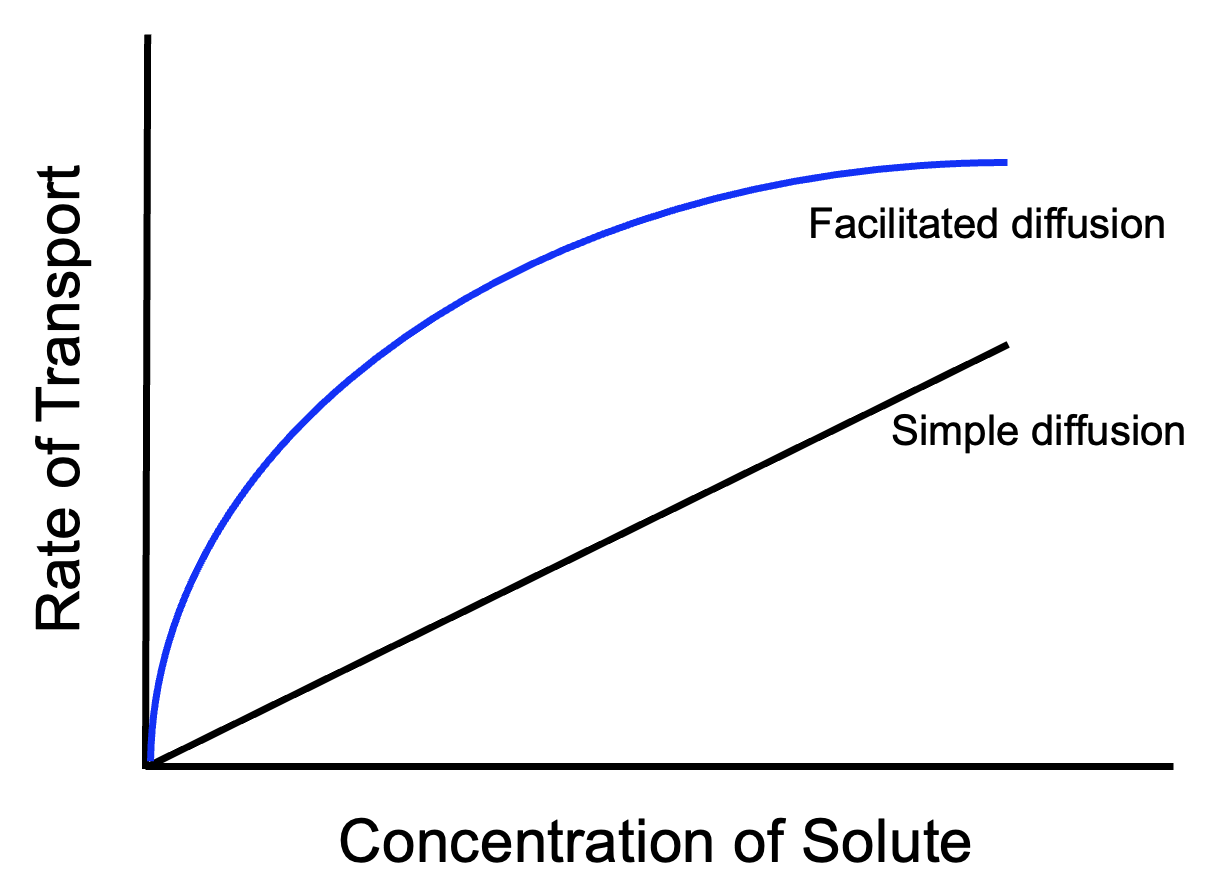

Active transport is easy to identify because it requires energy and transports against the concentration gradient. But is it possible to distinguish facilitated diffusion from simple diffusion?

Because facilitated diffusion is mediated by protein channels, and because the number of protein channels in a cell membrane is limited, facilitated diffusion shows saturation kinetics.

As the concentration difference across the membrane becomes greater, the rate of molecules diffusing across the membrane increases, for both facilitated and simple diffusion. However, facilitated diffusion through protein channels will reach a limit, at which point molecules are passing through all available protein channels as fast as they can. Further increases in the concentration of molecules cannot cause faster diffusion because every channel is busy and molecules have to wait for openings. For the same reason, active transport will also display saturation kinetics. Simple diffusion, though, will rarely reach a limit because in simple diffusion the entire area of the membrane is available.

Put it all together

Case study on Cystic Fibrosis

Molecular Fossils – lipid biomarkers worksheet

The slides for the lecture video clips on this page are in this file: membranes_transport

Works cited and resources

Allers, T, M Mevarech 2005. Archaeal genetics – the third way, Nature Reviews Genetics 6: 58-73 doi:10.1038/nrg1504

Cotton, JA, JO McInerney 2010. Eukaryotic genes of archaebacterial origin are more important than the more numerous eubacterial genes, irrespective of function, Proc. Natl. Acad Sci. USA published online before print doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000265107

Desmond, E, S Gribaldo 2009. Phylogenomics of sterol synthesis: insights into the origin, evolution, and diversity of a key eukaryotic feature, Genome Biol Evol 1: 364-381 doi: 10.1093/gbe/evp036

Lingwood, D, K Simons 2010. Lipid rafts as a membrane-organizing principle, Science 327: 46-50

Molecular movie of water molecule transport through an aquaporin channel, a process that takes about 12 nanoseconds on real time: waterpermeation

To test your understanding of transport processes, look at this teaching tidbit on Cell Membrane Permeability.

Sustainable Development Goals

UN Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 13: Climate Action – Variation in membrane lipid composition can affect the fluidity and integrity of membranes, which has implications for various biological processes, including adaptation to extreme environments. Studying the conditions under which organisms can withstand temperature changes can be beneficial in predicting which organisms and environments may be most at risk as temperatures rise.

A great application of fatty acid composition (ratio of saturated vs unsaturated fatty acids) to deduce historical temperatures from lake sediment cores: http://www.ldeo.columbia.edu/news-events/high-arctic-heat-tops-1800-year-high-says-study

This page explains the application of akenones in greater technical depth: http://chemoc.coas.oregonstate.edu/~fprahl/alkdesc.html

Story in NY Times about omega-3 fatty acids, Inuits and human evolutionary adaptations: http://www.nytimes.com/2015/09/22/science/inuit-study-adds-twist-to-omega-3-fatty-acids-health-story.html