Learning Objectives

- Outline the process of molecular cloning of a gene or segment of DNA

- Compare and contrast the process of PCR with DNA replication in a cell, including enzymes, primer nucleic acids, and temperature

- Describe appropriate methods for cloning eukaryotic genes so their protein products can be expressed (transcribed into mRNA, which is then translated to make protein).

- Interpret color change information for the lacZ/X-gal system for eukaryotic gene expression in bacteria

- Describe genome editing with CRISPR-Cas9, including the what is required for targeting the gene of interest and how target genes can be modified

Many of our drugs, much of our food, and even our clothing are now produced using recombinant DNA technology. Instead of depending on random mutation, and either natural or artificial selection, we now have the ability to directly manipulate the genes of organisms to create new proteins and new capabilities in our domesticated bacteria, fungi, plants and animals.

Molecular cloning

Molecular biologists coined the term “molecular cloning” to describe the process of selectively replicating a chosen segment of DNA. The cloned DNA segment may be replicated within a cell, using “recombinant DNA” technology, or in a test tube, using the polymerase chain reaction (PCR).

I. Recombinant DNA

Recombinant DNA technology leads to genetically modified organisms (GMOs). Recombinant DNA requires 3 key molecular tools:

- Cutting DNA at specific sites – most often performed by enzymes called restriction endonucleases or restriction enzymes. Restriction enzymes often make staggered cuts at specific 4, 6, or 8-bp palindromic sequences in duplex DNA, leaving characteristic “sticky ends” that can anneal to each other via hydrogen bonding between complementary bases on the single-stranded overhangs.

- Ligating DNA fragments with an enzyme called DNA ligase. DNA ligase, the same enzyme used during cellular DNA replication to knit together Okazaki fragments, creates covalent phosphodiester bonds between any two DNA fragments that have been cut by the same restriction enzyme, or have the same compatible “sticky ends”.

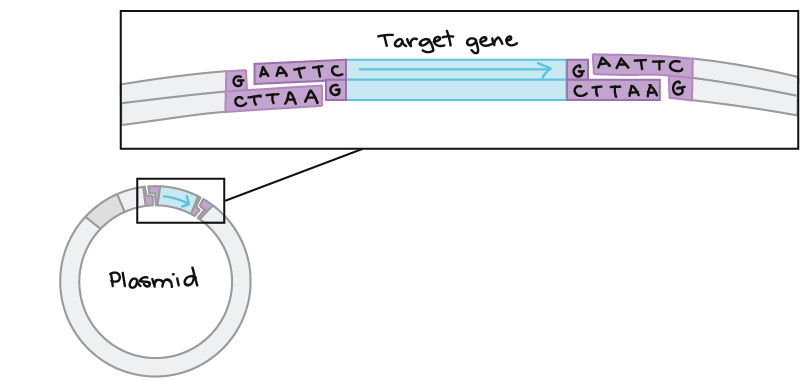

- A “vector”, such as a plasmid, that can be used to insert a new segment of DNA via restriction enzyme cutting and ligation. The plasmid containing the inserted DNA segment will replicate in host cells.

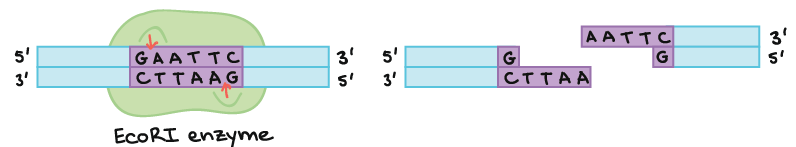

As an example of how a restriction enzyme recognizes and cuts at a DNA sequence, let’s consider EcoRI, a common restriction enzyme used in labs. EcoRI cuts at the following 6-bp palindromic site:

When EcoRI recognizes and cuts this site, it always does so in a very specific pattern that produces ends with single-stranded DNA “overhangs” or sticky ends:

If another piece of DNA has matching overhangs (for instance, because it has also been cut by EcoRI), the overhangs can stick together by complementary base pairing. Sticky ends are helpful in cloning because they hold two pieces of DNA together so they can be linked by DNA ligase.

Also see: https://www.dnalc.org/resources/3d/20-mechanism-of-recombination.html

II. Polymerase Chain Reaction

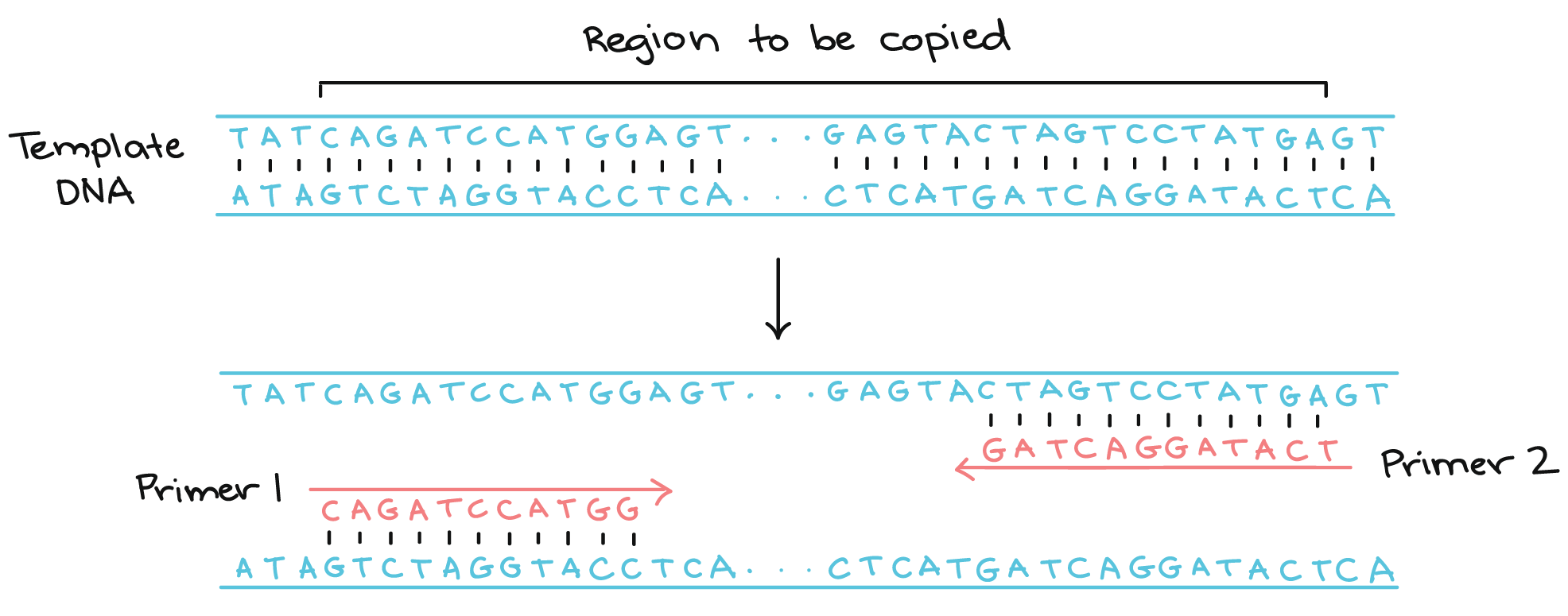

The alternative to using recombinant plasmids is to directly copy and amplify a specific DNA segment using PCR. Like DNA replication in an organism, PCR requires a DNA polymerase enzyme that makes new strands of DNA, using existing strands as templates and starting with a primer. The primer for PCR is a short sequence of DNA nucleotides selected by the experimenter, and it determines the region of DNA that will be copied, or amplified. Compare these details to DNA replication, where RNA primers are synthesized by the cell’s primase enzymes.

Two primers are used in each PCR reaction, designed so that they flank the gene of interest. The primers bind to the template by complementary base pairing.

When the primers are bound to the template, they can be extended by the polymerase, and the region that lies between them will get copied, duplicating the number of templates. PCR iterates this process 20-35 times, making millions of copies of the template.

A key difference between DNA replication and PCR is the thermocycling mechanism. In PCR, cyclical increases in temperature separate the double stranded DNA molecule, whereas in the cell, enzymes are used to unwind and unzip the DNA for the single round of DNA replication. This optional video shows the cyclical PCR process: https://www.dnalc.org/resources/3d/19-polymerase-chain-reaction.html

Even random DNA segments, where the base sequences are unknown, may be amplified by ligating adapter primers, short synthetic DNA segments of known sequence, to the ends of the target DNA molecules.

Gene size considerations for cloning eukaryotic genes

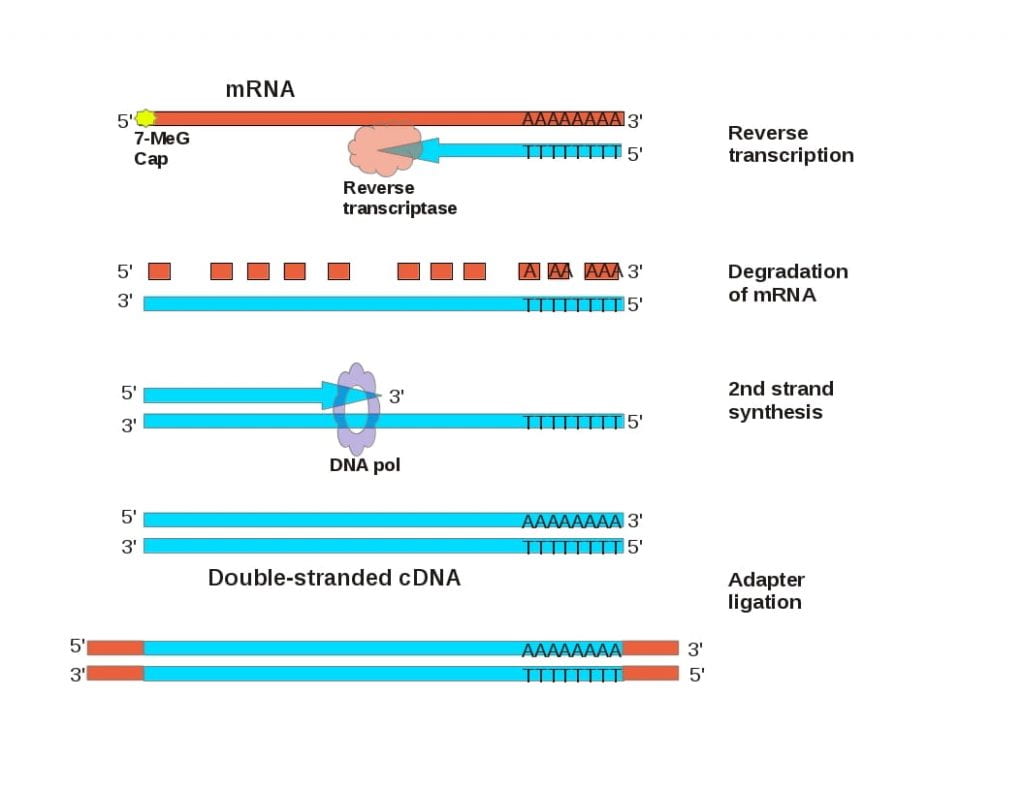

Molecular cloning of eukaryotic genes presents challenges because eukaryotic genes contain numerous, large introns. The introns increase the gene length beyond the practical size limit of plasmid vectors, which have a less than 10 kilo-base pairs (kbp). PCR is also difficult beyond about 10 kb. In addition, the bacteria used in molecular cloning cannot express a gene with introns.

However, the mRNA of a gene of interest lacks introns. mRNA is a compact version of a eukaryotic gene that retains all of the protein coding information, with the addition of a poly-A tail. The enzyme reverse transcriptase, along with an oligo dT primer (a string of Ts) that is complementary to the polyA tail, can be used to synthesize a complementary DNA (cDNA) molecule that contains coding regions without introns. Converting a gene of interest to cDNA makes it small enough that it can be cloned into a plasmid by ligating adapters that contain restriction endonuclease cleavage sites, or it can be amplified by PCR by ligating adapters that PCR primer sequences.

Expressing cloned genes in genetically modified organisms

A genetically modified organism (GMO) is any organism that has been manipulated to carry new genetic material, either from a different species or synthesized in the laboratory. The point of creating GMOs is usually to alter one or more traits in the modified organism, most often so they express a gene new to the organism. Examples include pathogen resistance or toxin expression to reduce herbivory.

Expression of foreign genes in bacteria

Plasmid vectors for cloning and expression in bacteria (see pUC18 map below) must have

- An origin of DNA replication (ori) that directs their replication in the bacterial (host) cell

- cloning sites (“polylinker” restriction endonuclease sites) that occur just once on the vector and allow insertion of cloned DNA segments

- a selectable marker gene, such as antibiotic resistance to ampicillin (ampR), so cells that do not contain the plasmid can be eliminated

- a way to distinguish cells that have the original plasmid from cells that have a recombinant plasmid, which in this case will involve screening for beta-galactosidase protein described below

- a promoter to drive transcription (and translation) of the inserted foreign gene

The last feature is important because the ligation of plasmid and foreign DNA segments favors the plasmid ends re-ligating without a foreign DNA insert, resulting in the original, “empty” plasmid with no foreign DNA insert. Plasmid vectors therefore have the cloning site within a second antibiotic resistance gene or within the lacZ gene (encodes beta-galactosidase). Insertion of a foreign DNA segment will disrupt the gene. Colonies of E. coli cells that have empty plasmids (no inserted foreign DNA) have an intact beta-galactosidase lacZ gene. The functional beta-galactosidase those cells produce cleaves a colorless dye called X-gal. Cleaved X-gal releases an insoluble blue dye, causing the cells to turn blue. E. coli cells that have plasmids with foreign DNA inserts cannot make beta-galactosidase and are unable to cleave X-gal. These recombinant cells form colonies that are white in color. Blue colonies are discarded, and white colonies are picked for further testing.

Cloning into the 5′ end of the lacZ gene also means that the E. coli cell can express a protein encoded by the inserted DNA. The lac promoter provides a means to regulate transcription. When transcribed, protein coding sequences in the inserted DNA are expressed as a fusion protein that contains the first few amino acids of the E. coli beta-galactosidase gene followed by any amino acids encoded in the same reading frame by the inserted DNA sequence.

Expression of foreign genes in eukaryotes

In plasmids like pUC18, recombinant eukaryotic genes can be expressed in bacteria. To switch to recombinant DNA expression in eukaryotic cells, vectors to express foreign genes must provide appropriate eukaryotic promoters upstream of the cloning site for transcription by the eukaryotic host cell, as well as downstream polyadenylation and transcription termination signals. For single-celled organisms like yeast, as well as for cultured cells, bacterial plasmids containing foreign genes can be transformed into the eukaryotic cells. The plasmid DNA gets into the nucleus and inserts into random locations in the host cell’s chromosomes. However, the delivery of genes into the cells of a multicellular organism poses particular challenges and requires special vectors and delivery methods. We describe these challenges for one application, human gene therapy, in the next section.

Gene therapy

Gene therapy poses a special challenge in delivering recombinant DNA into host cells. Recombinant DNA technology can readily clone a functional copy of a defective gene and insert it into a vector with the correct regulatory sequences. But how can we deliver this functional gene into the cells of a person who has already been born? The most promising techniques use viruses as the vector. Viruses evolved to be highly efficient at delivering their own genetic information into host cells. Replacing the viral replication genes with a therapeutic human gene eliminates the ability of the virus to replicate, while co-opting the viral infection mechanism to deliver the therapeutic gene into the nuclei of host cells.

Even then, only a small percentage of cells are infected and repaired (remember these therapeutic viruses can’t replicate to infect other cells). Moreover, benefits of viral gene therapy are short-lived, as the “repaired” cells age, die and are replaced by genetically unmodified cells.

A promising solution to these challenges is to find and genetically modify stem cells, those cells that will continue to divide and replenish the body’s cells for the rest of the patient’s life. Genetically modified stem cells can be returned to the patient’s body and have the potential to supply and replenish genetically modified blood cells and tissues for the rest of the patient’s life.

Genome editing

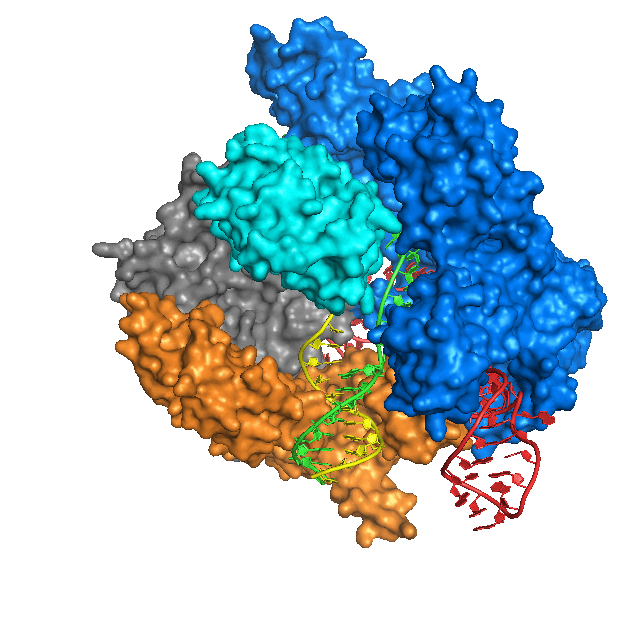

One newer technology becoming widely adopted in research labs around the world is CRISPR-Cas9, and variants. Adopted from a bacterial defense system, CRISPR stands for Clustered Regularly Interspersed Short Palindromic Repeats and functions as a library of foreign DNA samples that represent viruses or pathogens that could harm a bacterial species. Cas9 is a protein enzyme that binds short RNAs made from the CRISPR gene library. Cas9 bound to a short RNA can recognize corresponding DNA sequences that match the CRISPR RNAs, after which Cas9 will cleave or cut the DNA, causing a DNA break. The discovery of CRISPR-Cas9 from bacteria generated a molecular technology that enables researchers to delete, add, or replace particular bits of DNA in a cell.

Here is a TED talk video by Jennifer Doudna, one of the developers of CRISPR technology and a winner of the 2020 Nobel Prize for Chemistry:

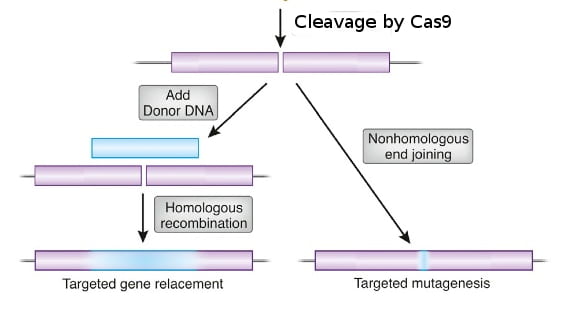

In essence, Cas9 is a protein that cuts DNA, which causes a DNA break. Whereas restriction endonucleases cut DNA at fixed sites, Cas9 is programmable to target a specific sequence of DNA. Cas9 targets the DNA site to be cut by using a short guide RNA (sgRNA). Cas9 binds the sgRNA and cuts DNA wherever the sgRNA binds to a complementary DNA sequence. So, in any organism where the genome sequence is known, scientists can make an sgRNA to target a particular DNA sequence in the genome, and Cas9 will cut the sequence, creating a double-strand DNA break. The cell’s DNA repair system will trim the broken ends of DNA and ligate them together in a process called non-homologous end-joining, which often creates a small deletion as a result of the trimming.

If instead a homologous DNA sequence that matches the sequences around the cut ends is available, the cell’s DNA repair system can use the matching DNA as a template to repair the break in the DNA. This homology-dependent repair system loops in the sequence information in the homologous DNA template to repair the broken DNA. By providing Cas9 protein, sgRNA, and a homologous template DNA that includes a desired change, scientists have successfully made precise changes in genomes of many kinds of cells and organisms, including cultured human cells.

As a society, we are currently debating whether human genome editing is less controversial than human genetic modification. In CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing, no non-human DNA need be added. The ethical discussions around gene editing in humans are especially contentious surrounding implanted embryos. The overwhelming majority of researchers believe the technology is not yet precise or accurate enough to attempt edits in human embryos in vivo. However, in 2018, Chinese biophysicist He Jiankui released claims of editing three human embryos that were then implanted and brought to term as live births. As a consequence, Chinese authorities reported they sent He to prison for three years.

Put it all together

In class we will discuss how these concepts are applied to current gene therapy methods undergoing research and development.

For optional additional information on these ideas, watch Dr. Choi’s lecture video on recombinant DNA technology (as one 39-min chunk; a copy of the slides can be found here: RecombinantDNA):

Sustainable Development Goal

UN Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 12: Responsible Consumption and Production – Biotechnologies can be critical in meeting UN targets to sustainably reduce waste generation, both from technological processes that are used to create products and in what we waste in our own homes (e.g. food wastes) from unsustainable lifestyles. Through careful development toward sustainable practices, new products and processes can improve the efficiency and sustainability of various industries, such as agriculture, energy, and medicine. The application of recombinant DNA technologies enables the production of precise proteins for medical and industrial applications. It also can help in the discovery of gene functions, which can be used to increased agricultural crop yields, mitigate losses inflicted by crop and human pests like mosquitoes, and even engineer organisms for biomedical study in the hopes of finding disease cures.

A good video explaining CRISPR/Cas technology:

http://www.ibiology.org/ibioeducation/crispr-a-word-processor-for-editing-the-genome.html

A new paper on inhibitors of Cas9, predicted as an evolutionary response by bacteriophage to inhibit cleavage of their genomes by Cas9: http://www.cell.com/cell/abstract/S0092-8674(16)31589-6